In This Episode

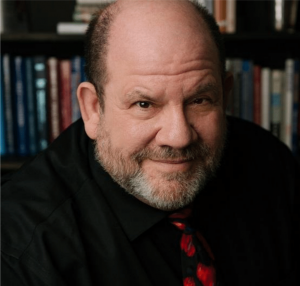

In this episode of the Helping Couples Heal podcast, Marnie and Duane talk with Stan Tatkin—clinician, researcher, teacher, and developer of the psychobiological approach to couple therapy (PACT). Stan leads a rewarding conversation about neuroscience and the role of attachment theory in healing betrayal and relational trauma.

Find information on our upcoming Workshop HERE.

Join our Private Facebook Community HERE.

To learn more about our coaching services, book a free 15-minute consultation HERE.

Powered by RedCircle

Stan begins with the story of his passion for couples therapy. He explains that his first experience working with couples was nightmarish, and it wasn’t until years later—after working with parent-infant pairs—that he found his calling in couples therapy. Stan then shares how he ultimately got into attachment theory. Attachment theory deals with the need to feel bonded and connected to the people in our lives. Children need to feel that bonding in order to survive. Beyond the body, our minds would not survive without interaction, so the attachment model confirms that humans need to attach to another person to develop healthy emotional lives. This is also key to our happiness, as one Harvard study determined.

But emotional understanding is not the end-all, be-all. If we allow our lives to be driven solely by emotions and feelings, we can expect our lives to follow the same track emotions do—up and down, like a rollercoaster. We need a purpose that ensures that love and connectedness will continue to build over time. This is where trust comes in.

In order for our relationships and connections to deepen, there must be a foundation of trust. In fact, people choose each other as life partners because of the agreed-upon principles that govern their relationship, whatever they may be. But when the foundational trust is broken through an act of betrayal, it can have dire consequences on the relationship. Betrayal shatters those unspoken, governing principles. Stan goes on to say that within the group (our relationships), we are considered special to each other, and so we are afforded special considerations, like always defaulting to the truth. These tolerances allow people to stay together and not go to war, but offending partners need to reckon with the extent of the damage done.

In certain kinds of betrayal, the brain is injured because the victim doesn’t actually know what’s true anymore—their world has been flipped upside down. This kind of earth-shattering trauma is so severe that it often results in PTSD. Partners should think of it as “a kind of soul-murder,” Stan explains. But not all is lost.

To the benefit of the couple dealing with such a circumstance, Stan lays out a couple of points for how the offending partner in any relationship can help—despite the fact that they will deservedly evoke the wrath of their partner. According to Stan, the first step for the offending partner is to table their own guilt, or else attempts to repair the relationship will fail. Because the hurt partner has no reason to believe them anymore, that foundational trust needs to be pieced back together again through routine demonstration—and it is possible to do this.

Marnie shares that she has never seen a relationship heal from betrayal when the offending partner is unable to understand the trauma caused by the betrayal. Those that can’t see the extent of the damage done cannot claw their way out. Stan completes the picture of what betrayal can do by suggesting that there is damage done to the self as well. Betraying a partner is the realization that one is unfit for a two-person system built on principles of trust. Stan explains that this grief must be present or else the betrayer will likely break trust again. People in serious relationships should really vet each other, Stan argues, for why they should be in a relationship at all. And in cases of severe relational trauma, the couples therapist is responsible for helping them develop a strategy to rebuild that trust.

Marnie urges that schools should teach children how to interact healthily in relationships. And because the culture, Stan points out, rewards lying and gaslighting, the couple with the betraying partner needs to develop their own culture between themselves.

Toward the end of the episode, Stan shares stories of survival. He explains that people, even in unlikely situations, will put off their own interests in order to survive. As a final point, Stan posits that the victim in the relationship must stand their ground—the relationship will not be able to move forward if the victim struggles to defend the protocols of trust. Attachment security is about parenting and boundaries. “We do not live in a world where we’re supposed to get away with everything,” Stan says. “And security in your relationship is dependent on understanding and respecting the boundaries that both parties have set up.”

On one last note, Marnie asks if there are any circumstances under which Stan thinks that a relationship cannot heal from past trauma. He answers that it ultimately comes down to established boundaries and shared principles. “Instead of repairing the boat, let’s rebuild the boat.” The betrayer cannot weaponize anything the victim has done, and they both have to agree to table those complaints for the sake of the restructuring and rebuilding process. If you can stick to this,” Stan says, “your relationship will be better than it ever was.” And to the perpetrator—“you get to be a better, wiser, happier person. And it’s worth it.” Trauma victims should seek couples therapy to renew themselves and to restore their relationships.

Please listen carefully to every word of this interview if you are someone who has betrayed your partner and can’t understand why she is as traumatized as she is by your betrayal.

Key quotes:

05:00 — “In adulthood, we both think we control our destinies.”

08:45 — “Our need for secure attachment is also actually vital for a happy and long life.”

11:20 — “Groups of people can easily become threatening if they don’t have a shared purpose.”

14:10 — “It’s this contract between us that sort of drives our relationship.”

18:00 — “The brain is going to be offline busy recalculating history. It’s going to be very busy for a very long time

in this new calculus to try to figure out what is reality again—that is PTSD.”

20:00 — “When this happens to a person, the structure of a person’s reality is shattered.”

24:00 — “The partner doesn’t understand what it will cost.”

28:30 — “Everything the partner does reminds them of the betrayal, and they have to understand that.”

33:00 — “The only way back in is to bear the scarlet letter.”

40:00 — “The lynchpin is that everything hinges on the victim. They have to take their place as holding all the power.”

43:00 — “You’ve already lost if your partner is not willing to do this.”

50:00 — “They are moving together or they don’t move.”

53:45 — “The greatest predictor of the outcome of betrayal is in the victim’s willingness to stand their ground.”

Rate and review us wherever you listen to podcasts!